Tales from Longford: The Forge

There has been a forge in the village of Longford in Middlesex, for centuries. The Forge building we can see today is not a listed building, but has been preserved because it is part of the street scene in the Longford Conservation Area. This is all that remains of a once larger complex of workshops, barn, house and three cottages

Before industrialisation, the agricultural village community was heavily reliant on the services of the wheelwright and blacksmith. He made the carts and ploughshares, and general repairs to equipment and gate hinges. He also shoed the horses who were the main power source on the farms. However one enterprising blacksmith went further.

In the eighteenth century Thomas Swain was making bells at the Longford forge. Thomas Swain was born in West Bedfont (on Heathrow airport’s southern border) and learned to make bells from Robert Catlin in St Andrew’s Holborn. He inherited the business of his master and moved the foundry to Longford in 1752. The type of bells Swain was making in Longford was called a crotal bell. A small spherical bell made by joining two semi-hemispherical pieces of metal, with an attachment at the top for hanging and a free-moving ball or “pea” enclosed. They were hung in clusters on horses’ harness and usually decorated with a pattern and the maker’s name. Occasionally metal detectorists still find bells with the initials TS which are attributed to him.[1] Later Swain was making large hanging bells for churches in London, Surrey and Sussex. These were made in situ in a large pit dug near the intended church in order to make transportation easier.[2] However Thomas Swain’s home and base was in Longford. The records show that Swain was paying window tax in Longford in 1766 and land tax in 1767. He died in 1782 and was buried in Harmondsworth churchyard on 26 April in an unmarked grave.

While Swain was away making church bells, by 1765 John Heath was the blacksmith and the wheelwright in the forge. He lived, with his wife and three children, in the house attached to the forge and workshop. On the night of 7 March someone broke into the wheelwright’s home, by making a hole in the plaster at the back of the building with a bill-hook, which was left at the scene. The next day John Heath noticed certain items missing from the shop, namely about ten shillings in halfpence and farthings, some worsted stockings, two canisters containing about a quarter of a pound of tea each, and a 30 pound lump of sugar all with a total value of thirty shillings. A 150 yards along the Bath Road from the Forge lived John Sharborn who had a questionable reputation, but John Heath was prepared to think well of people and did not get suspicious until he saw Sharborn in his Sunday best wearing a pair of stockings similar to the stolen ones. Heath obtained a search warrant from the local magistrate and went to Sharborn’s house with the Parish Constable, Matthew East. Mrs Sharborn was at home and stood by while the search took place. They found the stockings and the canisters of tea. John Sharborn was arrested and at his trial at the Old Bailey maintained his defence story of buying goods from a Scotch pedlar at his door, and produced a bill on which he said the pedlar had written. The Jury did not believe him and found him guilty of felony. He was sentenced to transportation and in September 1765 he was placed on the prison ship Justitia on a journey to Virginia in Colonial America. [3] It is not known what happened to Mrs Sharborn and her two small sons, but if she had no extended family to support her she was probably taken into the workhouse.

John Heath died in August 1782, soon after Thomas Swain. A local landowner, William Godfrey bought the Forge and rented out the whole complex, including three adjacent cottages, several brick-built stables, two orchards, and a meadow, to George Emmett.[4] After William Godfrey’s death in 1827 the business was bought by William Passingham, a wheelwright and Blacksmith in Harmondsworth village, who gave it to his son John to manage. John employed three men and one boy in addition to the family members. He married Ann Piecey and they had five daughters and two sons, John and William. As was the custom at that time the sons were expected to follow their father’s trade. These sons were apprenticed into the business, working with their father, but as the boys got older there was not enough work for all three of them in the business. The eldest son, John, married and moved to Slough, where he and his wife, Harriet, had a total of 14 children only seven of whom survived their childhood. John died in 1917.

His brother William stayed in Longford and in 1890 William was working, and living with his elderly widowed father who was becoming increasingly frail. When his father died in 1892 he was consoled by the close-knit Baptist community around him. Four years later, when William turned 40, he considered that as a successful businessman, and a respected member of the community, it was time to take a wife and maybe raise a family to inherit the business. He was attracted to a young widow who had fallen on hard times and they married in July 1896. Unfortunately for William she had lied about her age and was considerably older than he knew. Also, She was not used to country living and she found it hard to adapt to her new rural life. She began to drink heavily, neglected her household duties and declined in health. Eventually she had a fit and lapsed into a coma. Her husband sent for her father and they agreed that he and her mother should take her home to nurse her. This was the end of the marriage, but it didn’t end without a public scandal as each took the other to court and their marriage was publicly dissected. William couldn’t face the shame and soon after the final court case he said goodbye to the rest of his family and made for Southampton where he boarded a ship for Cape Town. It was a radical step to take, but his chagrin and humiliation left him little choice. Mrs Florence Passingham died in Bethnal House Asylum (Bedlam) in 1902. William Passingham died in Cape Town in 1927.

By then Ambrose Cure had bought the wheelwright and blacksmith’s premises and the goodwill of the business, still known as Passingham’s. Ambrose Cure was now in a position to marry, Maude, his sweetheart from London and they settled into the Longford community. However 31-year-old Ambrose Augustus Cure found his skills as a coach-builder were no longer required. The transport industry was in transition and horse-drawn vehicles were being superseded by bicycles and the internal combustion engine. By 1902, Ambrose Cure was selling up the plant and effects of the business to move abroad.[5] The couple emigrated to South Africa where he continued his trade as a blacksmith. They returned from Cape Town with their two small children in September 1904, but by the end of 1905 they set sail for Australia and arrived in Sydney after a voyage of 56 days.

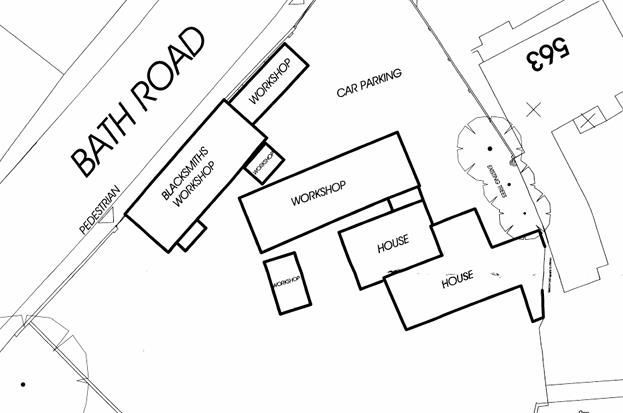

It was only after his arrival in Australia that Ambrose Cure decided to sell the freehold of the Longford premises. In June 1906, the property was up for sale. The freehold property consisted of a brick and slated 6-roomed dwelling-house with lean-to greenhouse, timber and tiled tool shed, large barn used as wheelwright’s shop, and farrier’s shop with furnace and large yard; together with 3 cottages adjoining.[6] With the proceeds of the sale Ambrose Cure brought a dairy farm in Byron Bay, New South Wales, where he died in November 1955.

In 1908 Mrs M.A. Bateman of Manor Farm, Harmondsworth, bought the Forge workshop complex for £675 which included the three thatched cottages that had been owned by her son-in-law Tom Adams. Tom Adams remained as tenant at the Forge and workshop and in 1913 was paying £15 a year rent on a 21 year lease, and living in Pine House behind the workshop. He lived there for the rest of his life. In January 1938 the three thatched cottages were condemned by the council as unfit for habitation and a clearance order was submitted to the Department of Health. The only form of sanitation for the three cottages were two pail closets. There was a public inquiry and protests from the long-time residents, but the demolitions still went ahead after the residents were given six weeks to vacate. The displaced residents were rehoused on the new council housing estate at Bell Farm in West Drayton.

Tom Adams, as well as being a blacksmith doing repair and bespoke work, was the son of a builder and carpenter, and he could turn his hand to any handyman task required by villagers. When Christopher Challis bought the neglected Weekly house in 1948 as a home for his young family, it was Tom Adams who helped him renovate and conserve the, now, Listed building for us to see today. Thomas William Adams died in 1962.

In 2006 the whole complex of forge buildings were redeveloped. The plan was to demolish all the main buildings, leaving just the small kerbside forge workshop. In the area behind this building were built two residential blocks. One with six studio flats, and one with six one-bedroom flats, and this is what we see today as Blacksmiths Court and Kings Court.

Like the whole village of Longford, (and most of Harmondsworth) this twenty-year-old development is under threat of demolition if the third runway is built at Heathrow airport. However, while the ancient blacksmith’s forge building exists we have a reminder of its contribution to village life over the centuries.

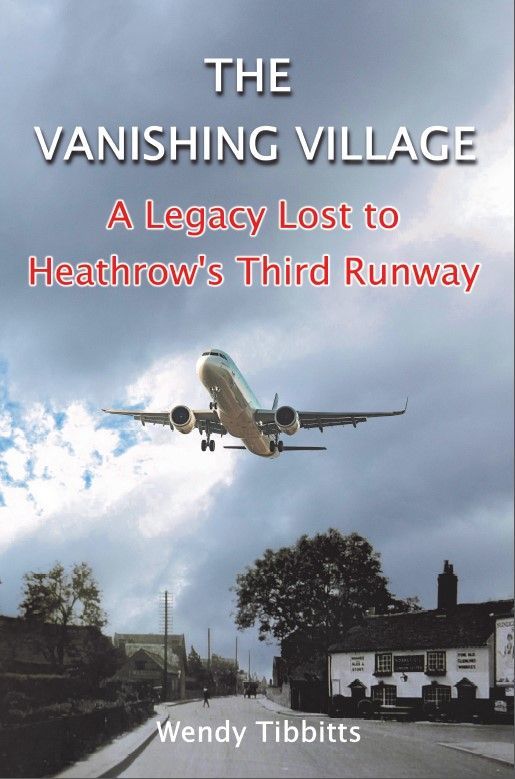

A fuller version of these, and other stories, about Longford appear in my book

“The Vanishing Village: A Legacy Lost to Heathrow’s Third Runway”.

[1] UK Detector Finds Database. http://www.ukdfd.co.uk/pages/crotal-bells.html

[2] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol2/pp165-168#fnn12

[3] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 09 January 2021), May 1765, trial of John Sharborn (t17650522-3).

[4] Morning Advertiser – Wednesday 16 May 1827.

[5] Uxbridge and W Drayton Gazette – Saturday 8 Marchg 1902.

[6] Uxbridge and West Drayton Gazette – Saturday 5 May 1906; ibid: Saturday 2 June 1906.